"Sant Jordi d'Alfama" Castle

THE ROMAN CAVE The Romans were not the first to occupy the lands of the region. Many centuries before, the cave artist of Cabra Freixet, in the present term of Perelló, left us a message painted on the rock, around a steep cliff that, seen from the sea, sailors caleros have imagined and named it as the Song of the Rooster. Much later, already in the 4th century before our era, the Ilercavons inhabited the Terres de l'Ebre, Iberian tribes that, like their neighbors Cossetants-Tarragonians, Edetants-Valencians and Ilergets-Lleidatants, all originated from the north of Africa and settled in the extensive territory that goes from the Coll de Balaguer to near Valencia. Roman writings tell us that the Ilercavons were good farmers, and also skilled sailors and fishermen. The Roman invaders and conquerors of Iberia laid out roads to dominate and administer the lands subject to the empire. One of them preserves a milepost (distance marking on a Roman road) found in Calafat, together with ceramic pieces and various coins. In Calafató, between Calafat and Sant Jordi, there are sections (today restored) of a Roman road. In front of Estany Tort, La Cala, Bon Capó and other submerged points, amphorae, anchors, a classic boat keel have been rescued, all half-hanging in sites that have not yet been inventoried or studied, but each even more depleted by the work of stealth divers. The Roman Dertosa (Tortosa) was attacked in 506 by barbarian armies from the north and would soon be plundered and ruled by the Visigoths, new lords of Hispania, but in the 8th century, the Arabs conquered it and established a form of life and civilization that lasted four hundred years, until medieval Christian Europe conspired to expel them from the Iberian peninsula. Count Ramon Berenguer IV subjugated these lands in 1148, the year in which the Tortoise Arabs surrendered. Later, the Catalan count-kings tried to populate the maritime strip that goes from the mouth of the river to the Coll de Balaguer, an attempt that did not progress, just as the royal will to populate the vicinity of Sant Jordi Castle was not fulfilled of Alfama. Before entering the second half of the 14th century, turtle fishermen asked the city for a license to fish in a cove that is between "lo Cap Roig and Sant Jordi", which could well be our Beach if we consider which, together with that of Sant Jordi, is the one that offers the best maritime protection on this stretch of coast. Also during these years there appeared a certain Pere d'Ametller, a citizen of Terrassa, who settled at a point on the coast near Perelló that has not yet been identified, called Port Mulné or Moliner (in the list of commanders of Sant Jordi who ruled the order for that time there is a certain Moliner), and there are already those who find a correspondence between the surname of that citizen and the name of Cala de l'Ametller or de l'Ametlla.

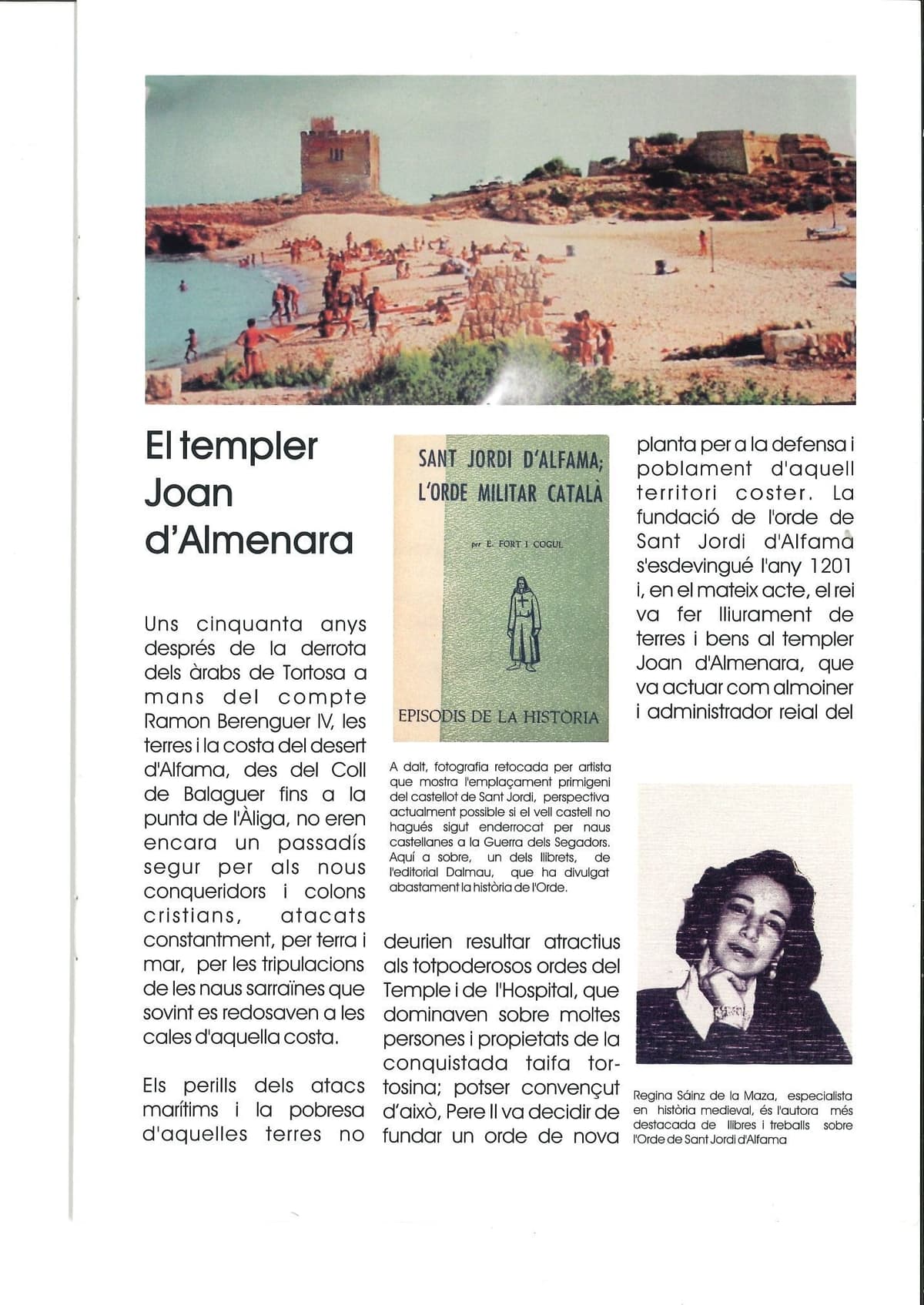

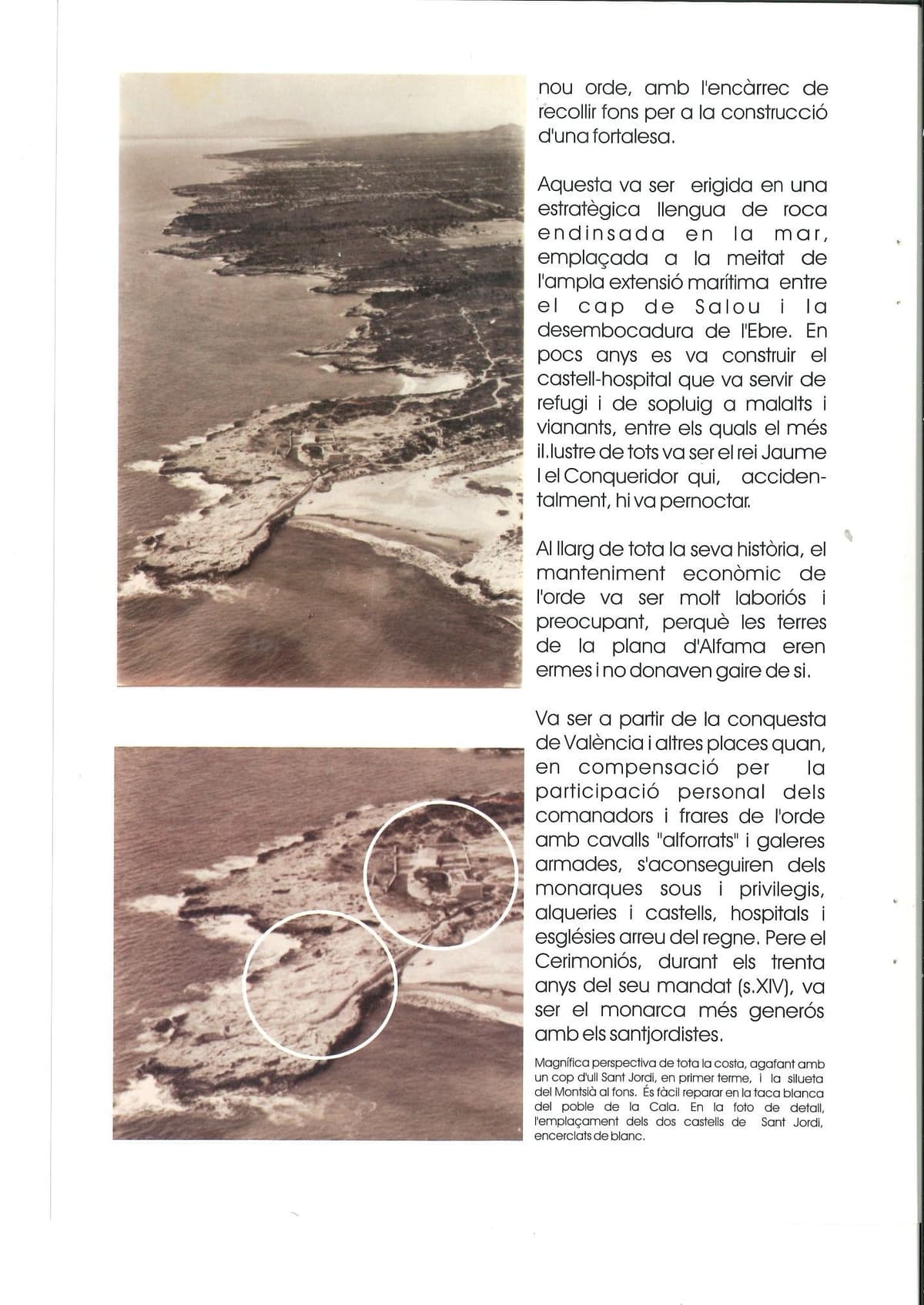

THE TEMPLAR JOAN D'ALMENARA Some fifty years after the defeat of the Arabs of Tortosa at the hands of count Ramon Berenguer IV, the lands and the coast of the Alfama desert, from the Coll de Balaguer to the tip of the Àliga, were still not a safe corridor for the new conquerors and Christian settlers, constantly attacked, by land and sea, by the crews of the Saracen ships that often sheltered in the coves of that coast. The dangers of maritime attacks and the poverty of those lands should not have been attractive to the all-powerful orders of the Temple and the Hospital, which dominated over many people and properties of the conquered Tortoise taifa; perhaps convinced of this, Pere II decided to found a new order for the defense and settlement of that coastal territory. The foundation of the order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama took place in 1201 and, in the same act, the king gave lands and goods to the Templar Joan d'Almenara, who acted as almoner and royal administrator of the new order, with the task of collecting funds for the construction of a fortress. This was erected on a strategic tongue of rock deep in the sea, located in the middle of the wide maritime extension between the head of Salou and the mouth of the Ebro. In a few years, the castle-hospital was built which served as a refuge and respite for the sick and pedestrians, among whom the most illustrious of all was King Jaume I the Conqueror who, accidentally, spent the night there. Throughout its history, the economic maintenance of the order was very laborious and worrisome, because the lands of the plain of Alfama were barren and gave a lot of life. It was from the conquest of Valencia and other places when, in compensation for the personal participation of the commanders and friars of the order with "freed" horses and armed galleys, they obtained from the monarchs salaries and privileges, farmhouses and castles, hospitals and churches throughout the kingdom. Pere the Ceremonious, during the thirty years of his mandate (14th century), was the most generous monarch with the Santijordistas.

CILIA AND THE SARRAINS Entering the 14th century, the center of power of the order and the residence of the commanders moved definitively towards the richest Valencian lands to the detriment of the interests and security of the territory and the castle of Alfama. The Sanjordist commander Humbert de Sescorts, who was a good warrior and navigator but a lousy administrator, appointed a prior for the church of Sant Jordi, property of the order in the city of Valencia. The Valencian priory fanned the flames of internal disputes and precipitated the decline of the house of Alfama. The good management of Guillem Castell and Cristòfor Gómez, leaders who succeeded him, did not manage to rectify the sad fate of the order. It was the year 1378. Sant Jordi's castle was over one hundred and fifty years old and the onslaught of time and the attacks of the Saracens had weakened its walls and ruined its fortress. Two armed Moorish galleys attacked the tower, captured and took Jaume Roger, commander of the castle, and his sister Cília to Bugia, an Algerian city. When King Peter the Ceremonious learned of the kidnapping, he sought by all means to collect the money for the rescue. Cília was released after two months, and devoted herself day and night to raising money to rescue her brother, but Jaume Roger was not released until three years later, once the captors had been given 450 gold florins. His successors feared that these mournful events would be repeated and, only due to the pressures of the king, who had the fortress repaired, and of his procurator in Tortosa, a city very interested in the defense of that place to safeguard its maritime trade and fluvial, it was possible that the tower was not abandoned. Little by little, they were losing their assets and consuming the income that the order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama had in Aragon, Valencia and Mallorca in order to survive. The behavior of the friars was also relaxing, such as that of some who wandered around the area and throughout the kingdom doing mischief and wasting the alms they collected. Neither the donations of the kings nor the papal indulgences in favor of the order nor the protection that Benedict XIII, the famous Luna Pope, always gave him, nor the repeated royal recommendations sent to popes, bishops, clergy, judges and lords could prevent the disintegration of the order and the patent decay of the tower. The appointment of a man from the region as master of the order, the Tortoise citizen Francesc Ripollés, to revive the institution and keep the fortress standing, was not successful, and after five years in the position, in January of the year 1400, he was accepted to resign his master's degree so that the path to the merger of the Order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama with the Levantine order of Sant Maria de Montesa was free.

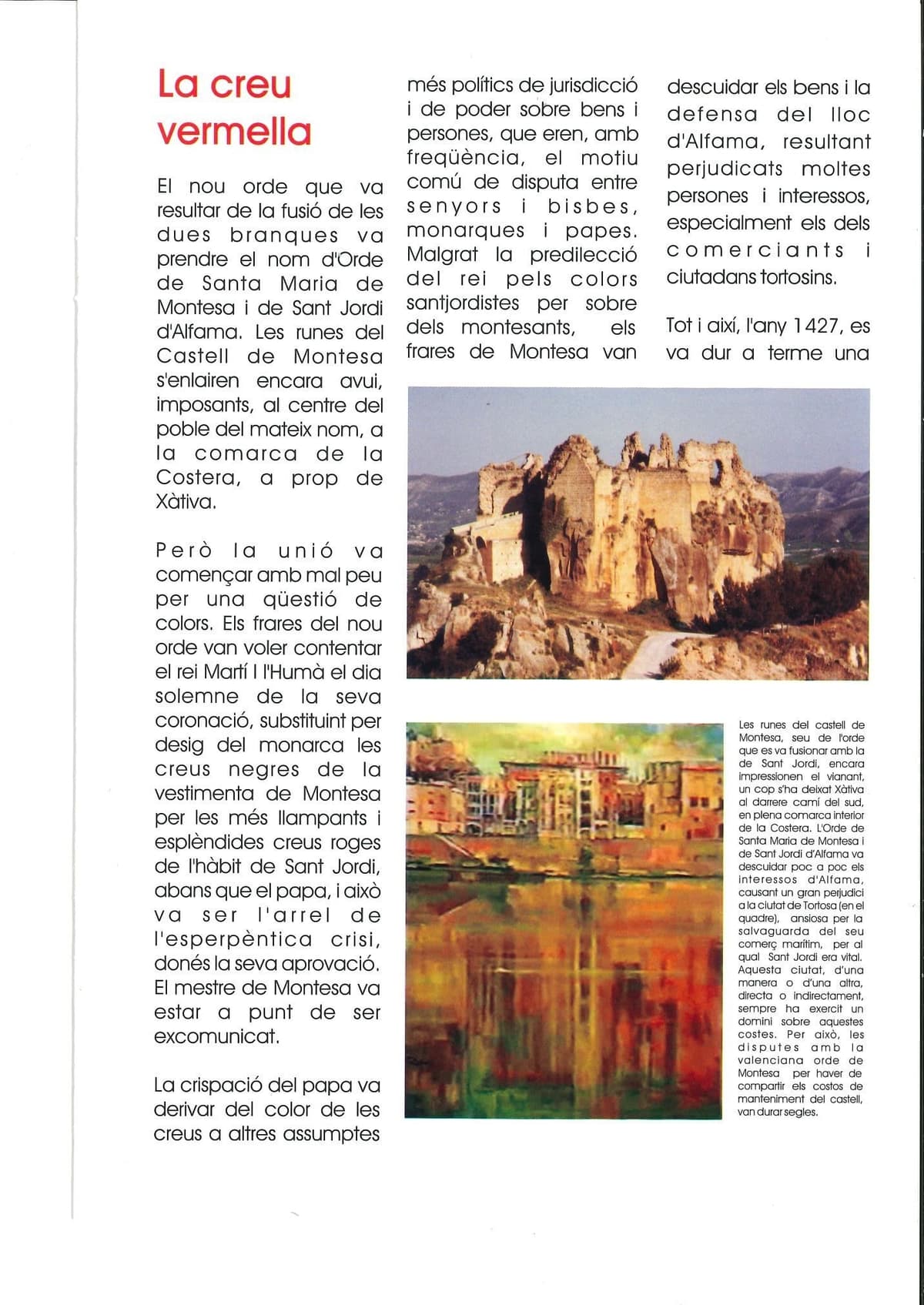

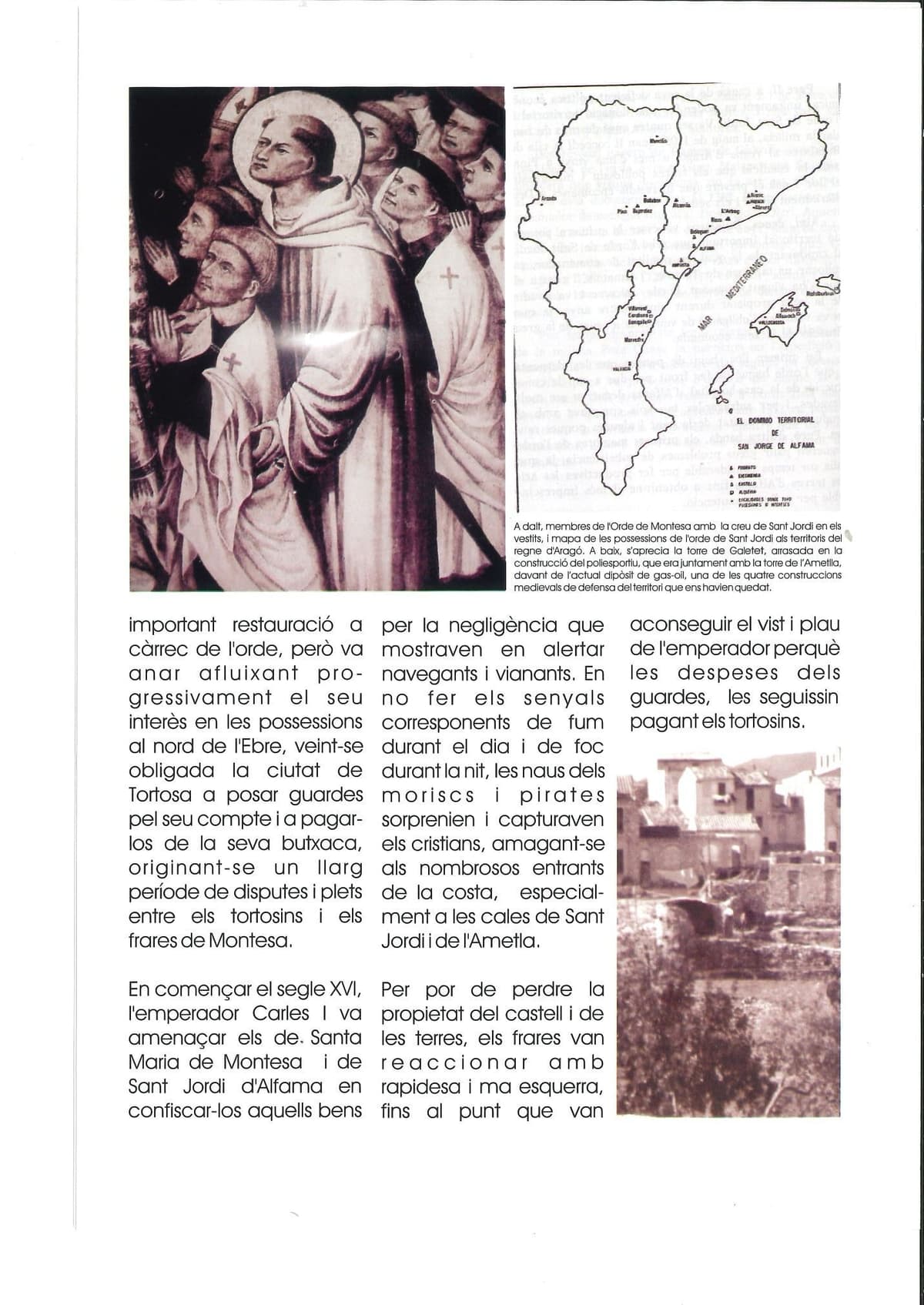

RED CROSS The new order that resulted from the merger of the two branches took the name of the Order of Sant Maria de Montesa and Sant Jordi d'Alfama. The ruins of Castell de Montesa still stand imposing today, in the center of the village of the same name, in the region of La Costera, near Xàtiva. But the union got off to a bad start because of a color issue. The friars of the new order wanted to please King Martí I l'Humà on the solemn day of his coronation, replacing at the monarch's request the black crosses of Montesa's vestments with the more striking and splendid red crosses of the habit of Saint Jordi, before the pope, and this was the root of the terrifying crisis, gave his approval. The teacher of Montesa was about to be excommunicated. The Pope's tension derived from the color of the crosses to other more political jurisdiction and power over goods and people, which were, frequently, the common reason for dispute between lords and bishops, monarchs and popes. Despite the king's predilection for Santjordist colors over montesants, the Montesa friars neglected the goods and the defense of the place of Alfama, resulting in harm to many people and interests, especially those of Tortosin merchants and citizens. Even so, in 1427, an important restoration was carried out by the order, but its interest in the possessions north of the Ebro gradually weakened, and the city of Tortosa was forced to put guards on their own and to pay them out of their own pockets, giving rise to a long period of disputes and lawsuits between the Tortosians and the Montesa friars. At the beginning of the 16th century, the emperor Charles I threatened those of Sant Maria de Montesa and Sant Jordi d'Alfama by confiscating those goods because of the negligence they showed in alerting navigators and pedestrians. By not making the corresponding signals of smoke during the day and fire during the night, the ships of the Moors and pirates surprised and captured the Christians, hiding in the numerous inlets of the coast, especially in the coves of Sant Jordi and the 'Almond. For fear of losing ownership of the castle and the lands, the friars reacted quickly and left, to the point where they got the approval of the emperor so that the expenses of the guards would continue to be paid by the Tortosins.

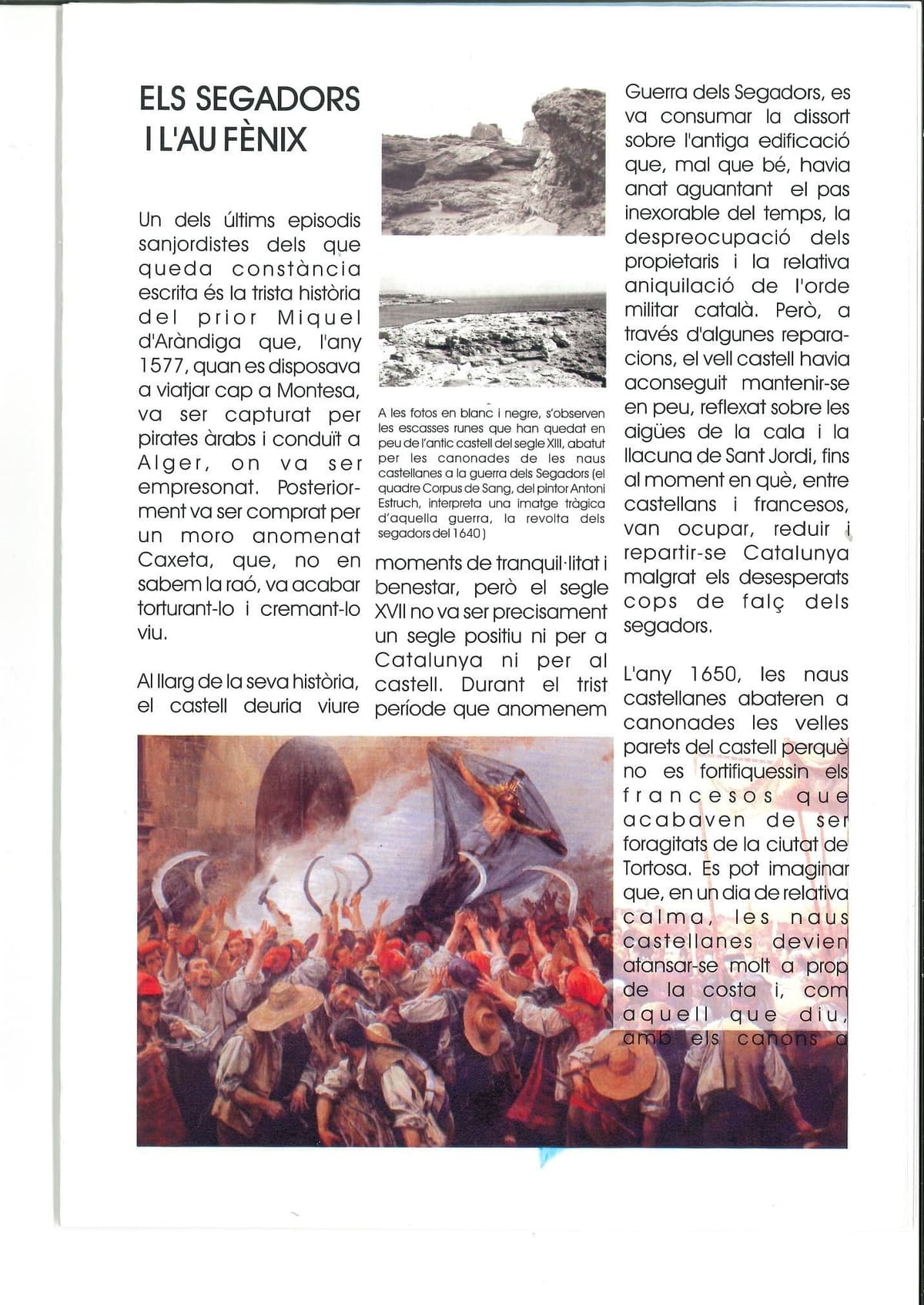

THE REAPERS AND THE PHOENIX One of the last Sanjordist episodes of which there is written evidence is the sad story of Prior Miquel d'Aràndiga who, in 1577, when he was preparing to travel to Montesa, was captured by Arab pirates and taken to Algiers, where he was imprisoned He was later bought by a Moor called Caxeta, who, we don't know why, ended up torturing him and burning him alive. Throughout its history, the castle should have experienced moments of tranquility and well-being, but the 17th century was not exactly a positive century for either Catalonia or the castle. During the sad period that we call the War of the Reapers, the disaster was consummated on the old building which, for better or worse, had endured the inexorable passage of time, the indifference of the owners and the relative annihilation of the Catalan military order. But, through some repairs the old castle had managed to stay standing, reflected on the waters of the cove and the lagoon of Sant Jordi, until the moment when, between the Castilians and the French, they occupied, reduced and distributed -se Catalonia despite the desperate scythes of the reapers. In 1650, Castilian ships blasted the old walls of the castle with pipes so that the French who had just escaped from the city of Tortosa could not fortify themselves. It can be imagined that, on a relatively calm day, the Castilian ships must have come very close to the coast and, as he says, with the cannons at bay, they must not have left many stones standing on that tower that , in the highest part, rose close to the ground, they must not have left many stones standing from that tower which, in the highest part, rose nearly twenty meters above the rocky tongue that had served it of only The Castilians' tactical decision once again left the coast unprotected and, thirty years later, King Charles II decided to rebuild the fortress. But its state must have been so deplorable that it was decided to build, already in the middle of the 18th century, a new building in a nearby place, a little more removed from the coast. However, anyone who looks at the walls of this building today will discover that it is largely built with ashlars from the old castle. That is why, like the phoenix, the medieval fortress has somehow survived the ashes of destruction.

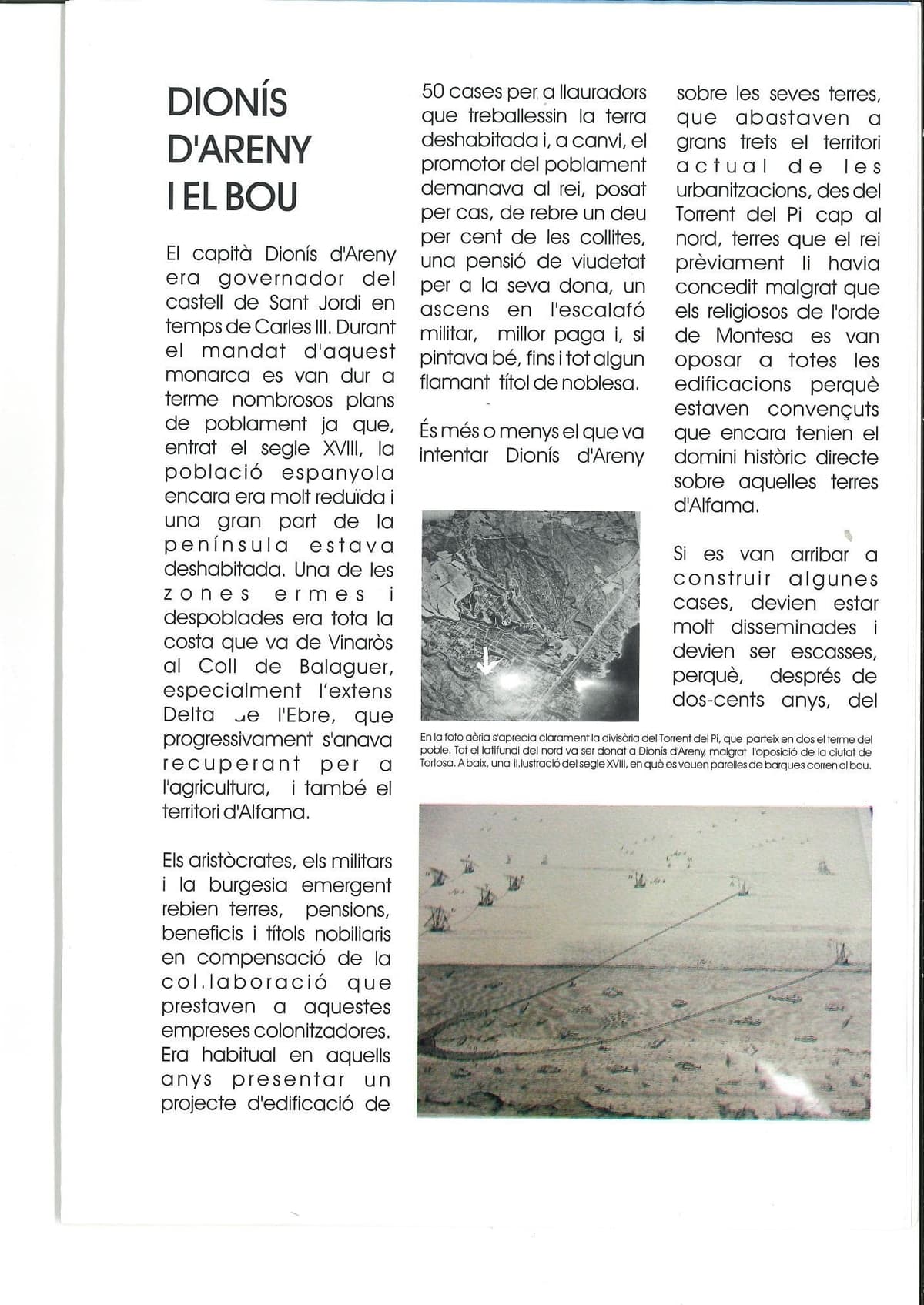

DIONÍS D'ARENY AND THE OX Captain Dionís d'Areny was governor of Sant Jordi Castle in the time of Charles III. During the mandate of this monarch, numerous settlement plans were carried out since, at the beginning of the 18th century, the Spanish population was still very small and a large part of the peninsula was uninhabited. One of the barren and depopulated areas was the entire coast from Vinaròs to the Coll de Balaguer, especially the extensive Delta de l'Ebre, which was gradually being recovered for agriculture, and also the territory of Alfama. Aristocrats, the military, and the emerging bourgeoisie received lands, pensions, benefits, and titles of nobility in exchange for their collaboration with these colonizing enterprises. It was common in those years to present a building project of 50 houses for farmers to work the uninhabited land and, in return, the promoter of the settlement asked the king, just in case, to receive ten percent of the crops, a widow's pension for his wife, a rise in the military ranks, better pay and, if he looked good, even some brand new title of nobility. This is more or less what Dionís d'Areny tried on his lands, which roughly encompassed the current territory of the urbanisations, from the Torrent del Pi towards the north, lands that the king had previously granted him despite the fact that the religious of the order of Montesa opposed all the constructions because they were convinced that they still had direct historical control over those Alfama lands. If some houses were built, they must have been very scattered and must have been few, because, after two hundred years, there is no trace of the neighborhood of Sant Jordi, although traces of a wide closed next to the new castle could clearly be observed until the 60s of the 20th century. But Dionís d'Areny was careful to ask for another important compensation from the king (and interesting for the caleros), requesting a royal license to fish for bull in the seas between Santes Creus and Cape Tortosa. This new fishery, introduced by the Catalans to Spain, was beginning to be profitable and he hoped to obtain a good percentage of the catches brought to port by the fishermen.

We have the doubt whether Dionís d'Areny managed to build a village in our area and whether he carried out the fishing plans. Another question that we cannot know now is whether this initiative had something to do with the beginning of modern fishing activity (we say modern, because there was always some fishing activity on this coast) in gulf waters. In parallel, it can be ventured that Dionís d'Areny was an inducer or intermediary in the arrival of the first Valencian fishermen who, arriving at the end of the 18th century, can be considered the founders of our Cala de l'Ametlla. We cannot finish without referring to another fishing community rooted in our town, on Almadrava beach, mostly of Benidorm origin, who fished for tuna with an almadrava that was anchored in front of that beach also in the end of the 18th century, a community that, from the very beginning, must have been closely related to the other seafaring settlement of Cala de l'Ametlla.

CASTLE DAY The plain of Sant Jordi has always been a territory that the Caleros have considered their own, despite the fact that this large portion of the area has been a large estate in the hands of one or a few owners. The tourism of the 60s revalued the coastal strips and the owners of the plain decided to make it profitable, dividing it and urbanizing it, and many old paths and accesses to the coast were cut off. The people of L'Ametlla de Mar had more obstacles to get closer to those lands, coves and beaches and, little by little, a vacuum of citizen disinterest was dug which, among other things, allowed the degeneration of the current castle building. To shake the conscience of the Caleros, a group of citizens decided to reclaim the Sant Jordi Castle for the municipality in 1982, and a great popular day was celebrated there that still lasts. A little later, the castle became municipal property. A workshop school for young people restored practically the entire 18th century castle over the course of two years. It will also be necessary to carry out work on the ruins closer to the sea, the few that still remain of the 13th century castle, seat of the Order of Sant Jordi d'Alfama.